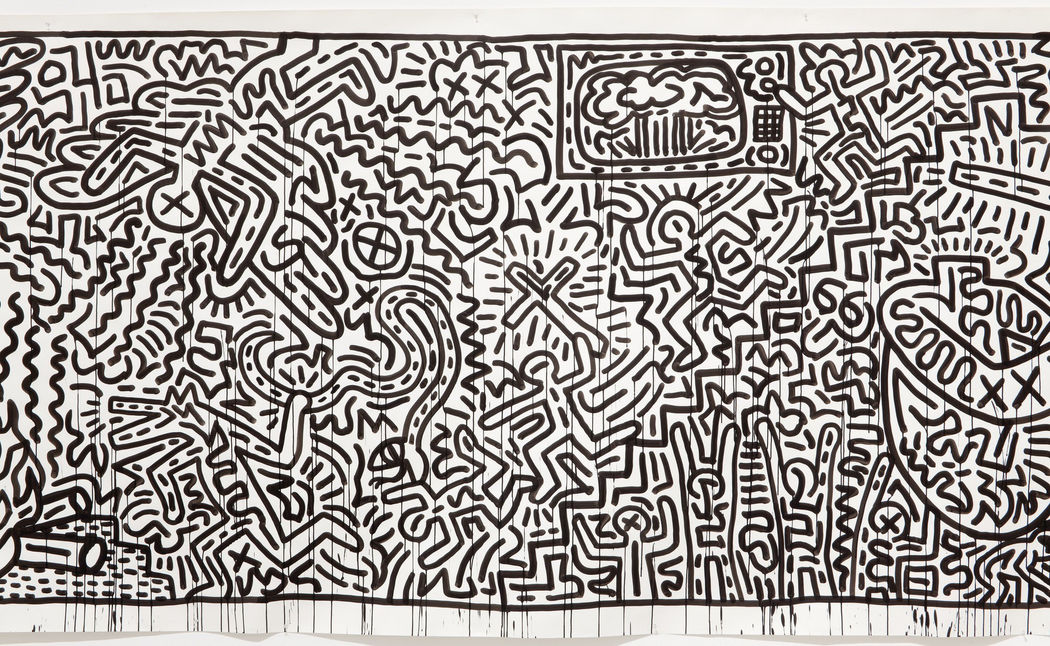

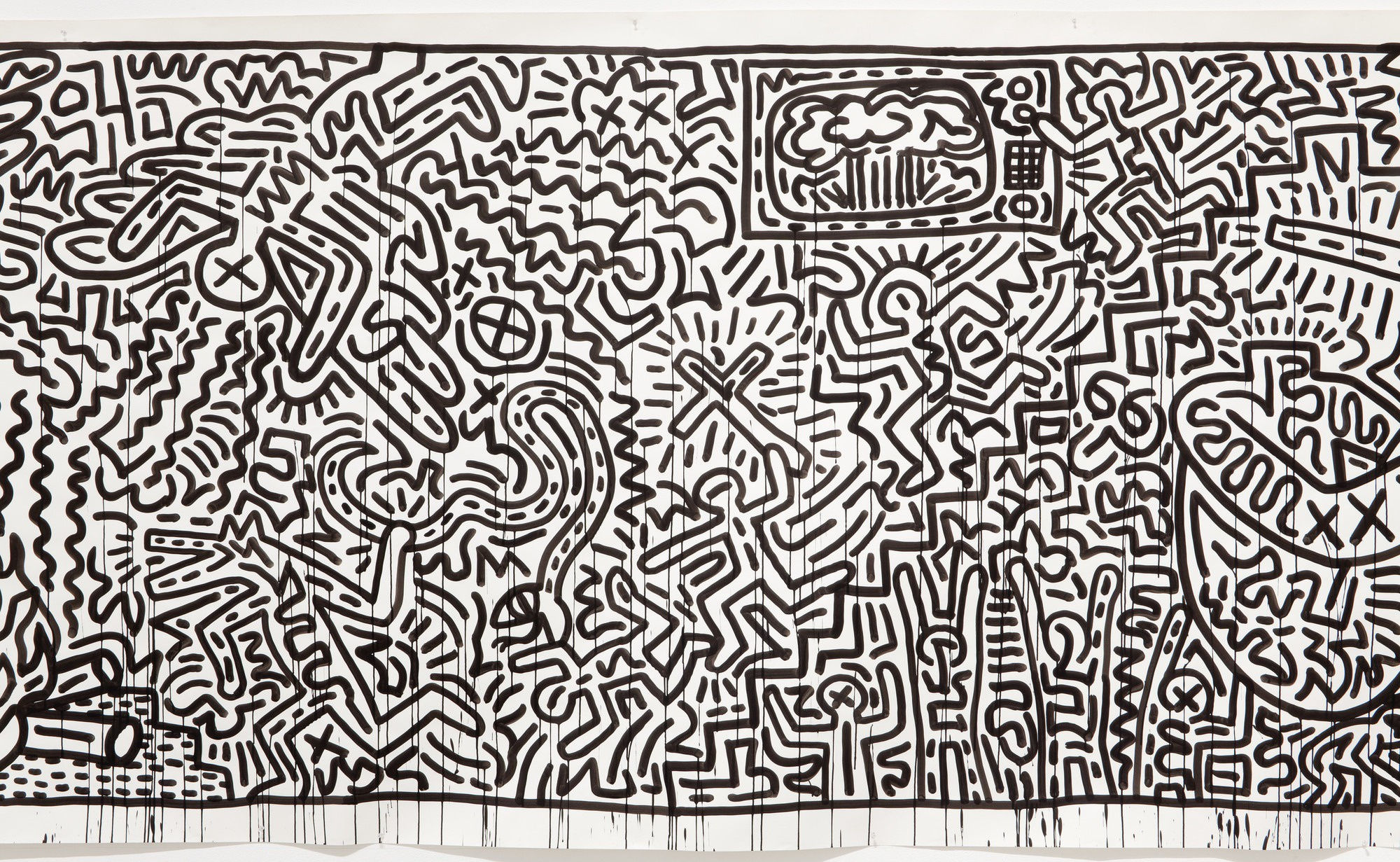

“Untitled" (1982)

In 1982, Haring created "Untitled," a powerful piece of anti-nuclear art that is emblematic of his anti-establishment and anti-war views. The artwork depicts an enthralled audience, eyes fixated on a television screen broadcasting an atomic mushroom cloud. The image underlines the passive absorption of viewers, consuming destructive imagery as though it were a regular show.

Haring believed in the transformative power of art to challenge social complacency. "Untitled" (1982) is an embodiment of this conviction. Through the medium of pop art, it castigates the culture of mass-media consumption that trivialised the horrors of nuclear warfare during the Cold War era. It's a stark reminder of the artist's belief in the pernicious effects of propaganda and our collective responsibility to question it.

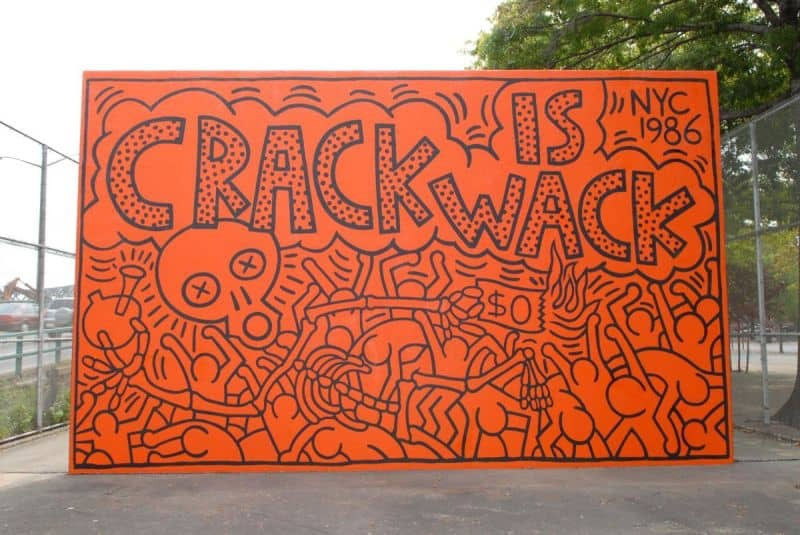

"Crack is Wack" (1986)

"Crack is Wack" is perhaps one of Haring's most well-known murals. It stands as an enduring commentary on the crack epidemic of the 1980s. Located on a handball court in New York, this towering mural was painted by Haring without official permission, as a response to the impact of the crisis on his community.

The mural features figures trapped within or tortured by the crack molecule, symbolising the drug's addictive nature and destructive consequences. His choice of a highly visible public space for this artwork underscores Haring's commitment to social activism, ensuring his message reached a wide audience. "Crack is Wack" became an emblem of resistance against the negligence of authorities in tackling the issue. It captures Haring's call to arms to eradicate drug abuse, reflecting the bold, direct confrontation of social issues that characterises much of his work.

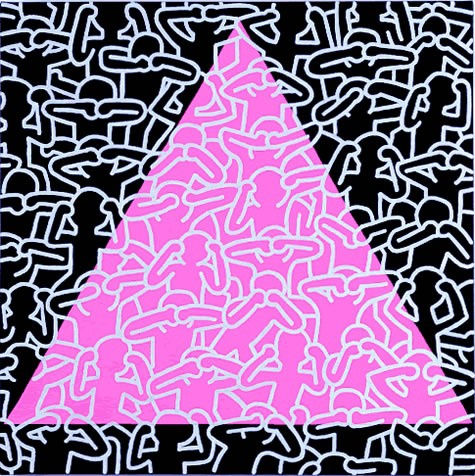

“Silence = Death" (1989)

This powerful work was created at the height of the AIDS crisis, a time when the artist himself was diagnosed with the disease. "Silence = Death" features Haring's iconic figures arranged around a pink triangle, a symbol reclaimed from its tragic historical usage to mark homosexual prisoners during the Holocaust.

Haring's artwork is a poignant critique of societal, political, and institutional silence in the face of the AIDS crisis. It powerfully advocates for awareness, conversation, and action in response to the pandemic. The work symbolises the artist's personal struggle as well as the larger fight against the disease, and the stigma and silence surrounding it. Today, it stands as a memorial of Haring's activism, and his commitment to the LGBTQ+ community's rights and health.

Michael Kimmelman, writing in The New York Times in 1990 says on Haring’s accessibility and popularity, “What can be said for Haring, and what separates his work from the mere vandalism of other graffitists, is that he had, like his friend Jean Michel Basquiat, an instinctive touch, and he developed a language of characters and forms unmistakably his own and far more visually arresting than the work of most cartoonists. Haring tended to reduce subjects to their most simple components: oppressor and oppressed, birth, death. His bold graphic style, snappy coloristic sensibility and penchant for a comic-book brand of narrative, so perfectly suited to the street and subway, also made ideal, if harmless, agitprop of the sort he turned out to warn against littering or to wish passers-by a happy new year.”

The development of his visually stimulating style allowed the diffusion of his messages in a symbiotic way. Images then message, message then image. Indeed, it was Haring’s ability to bypass the traditional gallery model for fine art that allowed him to share his political views with the masses. His radical means of communication, starting in the subways of NYC before taking on more expansive, bigger murals across the globe allowed his political views to reach an intended audience. Haring’s politics are not just the politics of the 80’s perhaps a reason behind his underlying and almost eternal relevance. Untied to either a time or location, Haring’s politics are politics for everyone, at everytime in every place. War, drugs and illness sadly seems to be tied to the human condition and have afflicted us since the first examples of human artistic expression in caves - proto-primitive styles that Haring himself almost recalls in his own hieroglyphs.

Keith Haring's art was far more than just visually stimulating; it was a form of political activism that shone a light on issues that were often overlooked or ignored. His works served as calls to action, rallying viewers to question societal norms and to strive for change. Whether he was condemning nuclear warfare, protesting the crack epidemic, or breaking the silence surrounding AIDS, Haring's art fought for justice and equality, leaving an indelible impact on the social and political landscapes of his time and beyond.

For more information on our Keith Haring original art for sale, contact Andipa via sales@andipa.com or call +44 (0)20 7581 1244.