Upon closer inspection, you'll notice subtle differences in this earlier rendition. Hockney's blue-eyed mother strikes the same graceful pose but wears a darker dress. His father, on the other hand, appears more restless and impatient, staring blankly into the distance, in contrast to the version displayed at the Tate where he is engrossed in a book. The most significant change is seen in the table mirror at the centre of the painting. In the earlier version, there is a self-portrait of the artist at the age of 40, showcasing his distinctive features: bleached-blond hair, owlish spectacles, and boldly patterned clothing. The only thing missing is a cigarette. A year later, Hockney replaced the self-portrait with a postcard featuring Piero della Francesca's "Baptism of Christ" from the National Gallery, casting himself as the saviour of painting. Hockney's self-belief and wit are evident in this transformation.

"My Parents and Myself" (1976) serves as a reminder that Hockney is not merely a commissioned portraitist catering to high society but an artist driven by intimate connections with his subjects. This exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery showcases the most intimate side of Hockney's work, featuring around 150 pieces spanning six decades but focusing on only five sitters, including his muse, Celia Birtwell, the textile designer. During his time in Paris in the mid-1970s, Hockney immortalised Celia in a series of exquisite drawings using Caran d'Ache coloured pencils, often depicting her in skimpy slips, negligees, and even in the nude, radiating the purity and brilliance of gold.

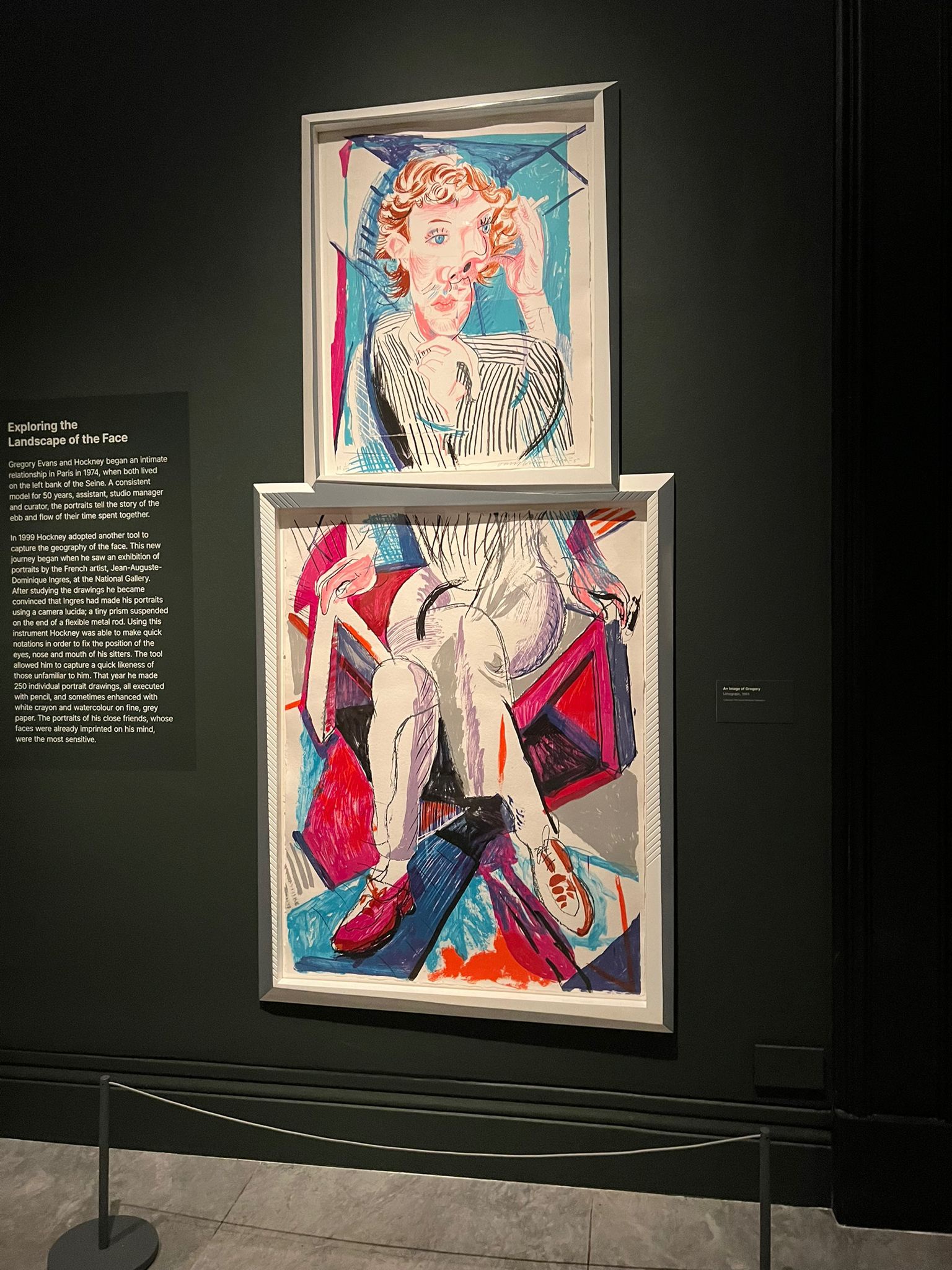

Elsewhere in the exhibition, we encounter a former lover who sits moodily on a crumbling column stump in Rome, and later, we see the same youth depicted asleep. This is Gregory, the melancholic counterpart to Celia's vivaciousness, easily recognizable by his lugubrious expression and distinctive pout. As the decades pass, and as this exhibition explores the theme of ageing, Gregory transforms from an ephebic lover boy, often seen wearing only bobby socks, to a bespectacled old man, slumped in an armchair, resembling a retiree engrossed in daytime television.

A small gallery within the exhibition pays tribute to Hockney's mother, portraying her as a serene figure with her hands gracefully arranged, unless she's engrossed in a crossword puzzle, causing her to sprout an extra arm and display a furrowed, thoughtful brow. Laura's depictions range from inscrutable and sphinx-like to wise and occasionally sad, such as in a sepia drawing created on the day of her husband's funeral. These portrayals emphasise the intimacy of Hockney's connection with his subjects.

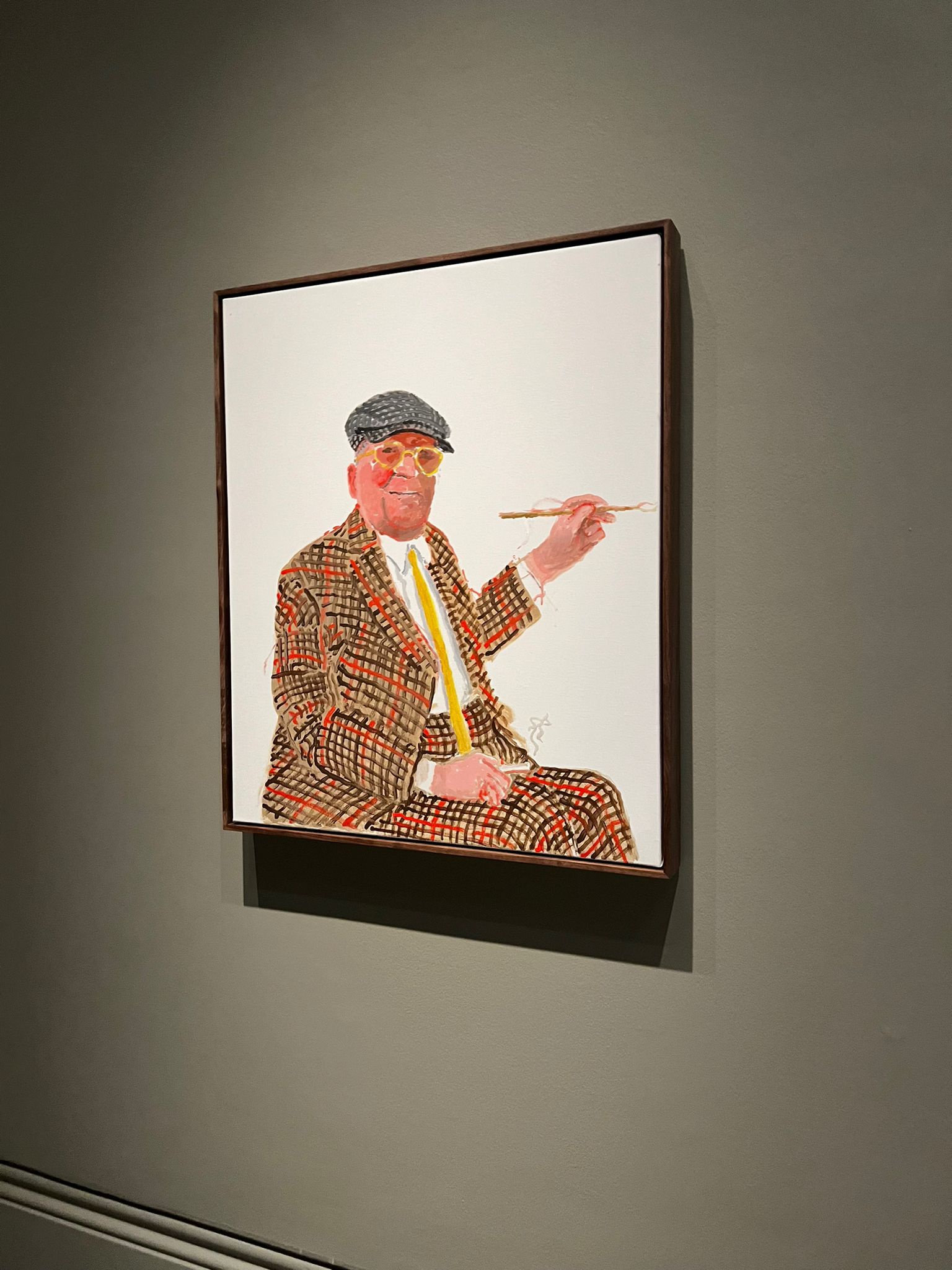

The exhibition also delves into Hockney's self-portraits, which form a compelling subplot in his artistic journey. From his early years as a nerdy-looking Yorkshire kid with a pudding-bowl haircut to his later embrace of his identity and style, Hockney's evolution is on display. His admiration for Picasso's self-promotion is evident, and he skillfully uses his trademark spectacles in playful ways, like placing them atop a half-finished doodle of his face to create a nose.

This exhibition challenges several common misconceptions about Hockney's art. Contrary to the popular belief that he exclusively paints swimming pools, this showcase features only one such work. Additionally, Hockney's supposed obsession with modern technology is debunked, as his art remains fundamentally traditional and conservative, despite occasional experiments with technology.

Hockney's dedication to observing his subjects and capturing their essence using hand and eye alone is highlighted. He resists contemporary art trends, which may explain his enduring mainstream popularity. However, the exhibition also reveals moments of vulnerability and inconsistency in his work, such as weaker drawings from 1994 and lifeless creations using an optical device called a "camera lucida."

In the final gallery, Hockney presents a few recent portraits, but the magic that characterised his earlier works seems to have diminished. These portraits, while still reflecting the personalities of his subjects like Celia, come across as somewhat uninspired, lacking the depth and refinement of his earlier pieces. Hockney's art, it becomes clear, is best suited to representing youth with its ethereal refinement and radiant sunlight.

Buy David Hockney signed prints at Andipa Editions and speak to our team via sales@andipa.com or call +44 (0)20 7589 2371 for more information.